Committals: Issues Paper (html)

3. Victoria’s committal and pre-trial system

Introduction

3.1 This chapter describes Victoria’s committal and pre-trial system. A summary of significant data is provided after this introduction and illustrative data is set out where relevant throughout the chapter.

3.2 In Victoria, criminal offences are categorised as:

- summary offences—generally less serious charges that are heard and determined by a magistrate alone

- indictable offences—serious offences that are heard and determined in either the County or Supreme Courts before a judge and jury

- indictable offences that may be heard and determined ‘summarily’ (in the same way as summary offences).

3.3 All offences, regardless of category, start in the Magistrates’ Court. Summary offences, and most indictable offences that may be heard and determined summarily, are dealt with in the Magistrates’ Court.

3.4 Indictable offences are heard either by guilty plea, or trial before a jury, in the County or Supreme Court. Before an indictable offence is transferred to a higher court, the case goes through a committal proceeding in the Magistrates’ Court.

3.5 The only indictable offences that do not go through a committal proceeding are cases where either:

- the Director of Public Prosecutions (the DPP) files a ‘direct indictment’

- the charge is appropriate to be heard and determined summarily and the accused person consents to this.

Summary of significant committal data

3.6 In 2017–18:

- 3426 cases commenced in the committal stream of the Magistrates’ Court

- approximately one-third of committal stream cases were either dealt with summarily or withdrawn by the prosecution

- of the cases dealt with summarily, 44 per cent resolved summarily at a committal mention, and 42 per cent resolved summarily at a committal hearing

- around two–thirds of all committal stream cases, including those dealt with summarily and those committed to higher courts, involved a guilty plea prior to committal

- 71 per cent of committal stream cases were committed to a higher court, either for trial or sentence

- of the cases committed to a higher court, 46 per cent were committed on the basis of a guilty plea

- when cases are committed to a higher court at a committal hearing, the median number of days they spend in the Magistrates’ Court is 228

- when cases are committed to a higher court at a committal mention, the median number of days they spend in the Magistrates’ Court is 107

- there were ten committal stream cases where a magistrate discharged all charges (so none were committed to a higher court) and 57 cases where some charges were discharged and some were committed to a higher court

- the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) filed 19 direct indictments.

Purpose of committal proceedings

3.7 Section 97 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic) (CPA) outlines the purposes of committal proceedings:

- to determine whether a charge for an offence is appropriate to be heard and determined summarily

- to determine whether there is evidence of sufficient weight to support a conviction for the offence charged

- to determine how the accused proposes to plead to the charge

- to ensure the prosecution case against the accused is adequately disclosed

- to enable the accused to hear or read the evidence against them and to cross-examine prosecution witnesses

- to enable the accused to adequately prepare and present a case at an early stage

- to enable the issues in contention to be adequately defined.

3.8 These statutory purposes are broadly consistent with the common law characterisation of the purposes of committal proceedings as ‘an important element in the protection which the criminal process gives to an accused person’.

Charging practices and the decision to prosecute

3.9 Initial responsibility for investigating most criminal offences, and for filing charges, lies with Victoria Police. The police officer who investigates and charges a person with a criminal offence, known as the ‘informant’, must comply with statutory requirements imposed by the CPA. In addition, the Victoria Police Manual (VPM) requires the informant to:

Ensure there is sufficient admissible evidence to cover all points of proof relevant to each charge and that there is a reasonable prospect of a conviction being secured.

3.10 Once charges are filed, most cases involving indictable offences are prosecuted by the Office of Public Prosecutions (OPP) on behalf of the DPP. Summary offences and most indictable offences able to be heard and determined summarily are prosecuted by Victoria Police.

3.11 Decisions relating to the prosecution of an indictable case, such as which charges proceed and what evidence is relied on, are guided by the Policy of the Director of Public Prosecutions for Victoria (the Director’s Policy). The Director’s Policy states that a prosecution must not proceed unless both of the following apply:

- there is a reasonable prospect of conviction

- the prosecution is in the public interest.

3.12 To determine whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction, a range of factors are considered, including:

- all the admissible evidence

- the reliability and credibility of the evidence

- the possibility of evidence being excluded

- any possible defence

- whether the prosecution witnesses are available, competent and compellable

- how the witnesses are likely to present in court.

3.13 The Director’s Policy prescribes that charges that do not have a reasonable prospect of conviction must be abandoned at the earliest possible stage.

Disclosure obligations

3.14 The Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) recognises that a person charged with a criminal offence in Victoria is entitled to be ‘informed promptly and in detail of the nature and reason for the charge’.

3.15 A ‘brief of evidence’ is prepared by the informant. This contains the evidence relied on by the prosecution.

3.16 The brief of evidence is crucial to the committal process, not just for the parties but also for the magistrate, as the decision whether to commit the accused for trial is based on the information it contains.

3.17 Depending on the case, the informant either prepares a ‘hand-up brief’ or a ‘plea brief’. A hand-up brief must include any information, document or thing that is relevant to the alleged offending. This includes items such as a copy of any witness statements made, a list of any things the prosecution intends to tender as exhibits, any record of the accused’s interview with police, and a description of any forensic procedure, examination or test that has not yet been completed and on which the prosecution intends to rely as tending to establish the guilt of the accused.

3.18 A plea brief, however, is prepared if the accused indicates an intention to plead guilty before the hand-up brief has been served. Less substantial than the hand-up brief, a plea brief need not contain all relevant material (as a hand-up brief does) so it can be compiled in a shorter timeframe.

3.19 The informant’s disclosure obligations under the CPA are ongoing. Any material required to be included in the hand-up brief which comes into the informant’s possession after service of the hand-up brief must still be provided to the accused, the DPP and the court.

3.20 While section 111 of the CPA makes specific reference to the informant’s ongoing disclosure obligations, the prosecution’s statutory disclosure obligations commence only once an accused has been committed for trial or a direct indictment is filed. At common law, however, ‘there is no distinction for disclosure purposes to be drawn between the prosecution … and the police informant’.

3.21 There are no corresponding disclosure obligations on an accused prior to committal. Once a matter has been committed to a higher court for trial, however, the accused must comply with disclosure obligations prescribed by the higher court’s practice directions, as well as a variety of notice requirements in the CPA and under the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic).

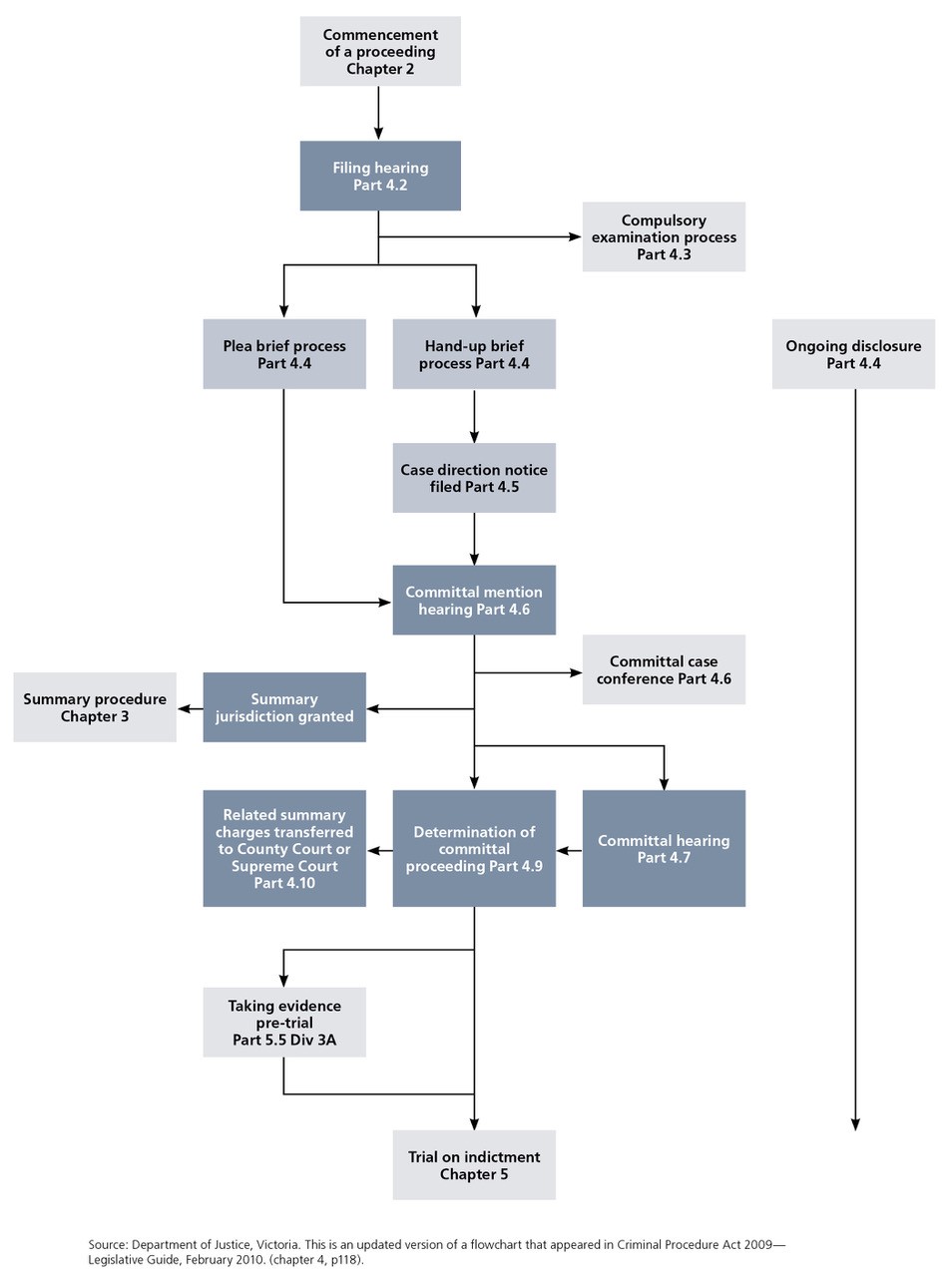

Figure 1: Court events and case management

3.22 This section discusses the variety of court events that make up the entire committal proceeding, including data relevant to each stage. The term ‘committal proceeding’ is used to refer to this process as a whole, whereas the term ‘committal hearing’ refers to the final court event, which often involves cross-examination of witnesses and a magistrate deciding whether to commit an accused person for trial.

3.23 All cases involving indictable offences, as well as some more serious cases involving indictable offences that can be heard and determined summarily, start in the ‘committal stream’ of the Magistrates’ Court.

3.24 Table 1 shows the number of cases that commence in the committal stream each year, and how many of these cases are committed to a higher court or finalised summarily.

Table 1: Determination of committal stream cases

| Committed to higher courts | Finalised summarily[1] | Total no. of committal stream cases |

|||

| No. of cases | % of cases | No. of cases | % of cases | ||

| 2013–14 | 2,263 | 72% | 871 | 28% | 3,134 |

| 2014–15 | 1,979 | 69% | 880 | 31% | 2,859 |

| 2015–16 | 2,029 | 71% | 825 | 29% | 2,854 |

| 2016–17 | 2,253 | 71% | 929 | 29% | 3,182 |

| 2017–18 | 2,432 | 71% | 994 | 29% | 3,426 |

[1] The number of cases dealt with summarily includes cases where an indictable charge that cannot be determined summarily is withdrawn by the prosecution and there are no other charges that are required to be determined by the higher court, as well as cases where all charges (indictable and summary) are withdrawn by the prosecution: ibid.

Filing hearing

3.25 A committal proceeding commences at a filing hearing in the Magistrates’ Court. This administrative hearing sets dates for service of the hand-up brief and a committal mention hearing, along with any other appropriate orders or directions.

Compulsory examination hearing

3.26 At any stage after filing a charge against an accused, but before a committal hearing, the informant may seek an order requiring a person to attend court for examination, or to produce a document or some other thing. A compulsory examination hearing can occur after the committal mention hearing only if the magistrate is satisfied that it is in the interests of justice.

3.27 Compulsory examination hearings are most commonly used when a prosecution witness has refused to provide a written statement. The transcript of the compulsory examination hearing then constitutes the evidence of that witness and forms part of the brief of evidence.

Special mention

3.28 A special mention may be held at any time during committal proceedings to allow a magistrate to amend the date of any hearing, conduct a committal mention, determine a committal proceeding, or make other orders or directions as appropriate.

Committal case conference

3.29 A magistrate may direct the accused and the prosecution to participate in a committal case conference. Committal case conferences should be held on the committal mention date wherever practicable.

3.30 Committal case conferences aim to reduce the number of committal proceedings which resolve at the door of the court by providing ‘a more informal opportunity for the prosecution, the defence and the court to discuss the case and attempt to identify the key issues to be resolved’.

3.31 Evidence of anything said or done in the course of a committal case conference is not admissible in any later proceeding unless all parties to the conference agree.

3.32 The Magistrates’ Court Practice Direction 7 of 2013 currently restricts the use of committal case conferences to cases involving offences against the person, as well as armed robbery and aggravated burglary.

Committal mention

3.33 The committal mention is the central case management hearing in committal proceedings. At this hearing, the magistrate may commit the accused for trial in a higher court, offer a summary hearing, determine an application for leave to cross-examine a witness, or make other appropriate orders or directions.

Case direction notice

3.34 A case direction notice, often referred to as a ‘Form 32’, is a document filed jointly by the parties with the Magistrates’ Court. Its purpose, among other things, is to indicate to the court how the case is to proceed.

3.35 Requiring the parties to jointly file this notice ensures the legal practitioners involved in a case will engage in discussion prior to the committal mention hearing. The purpose of this discussion is to lead to resolution of the case or identification of relevant issues.

3.36 The case direction notice must be filed seven days prior to the committal mention hearing and must include:

- the procedure proposed for dealing with the matter

- if the parties have not reached agreement, details of the issues which have prevented the case from resolving

- the names of any witnesses the accused seeks to cross-examine, and for each witness:

– the issue which will be the subject of cross-examination

– the reason the evidence is relevant to that issue

– the reason cross-examination on that issue is justified

– whether the informant consents to or opposes the proposed cross-examination, and if the informant opposes it, his or her reason for doing so.

3.37 The case direction notice can also be used by the accused to request further disclosure, including of any document or thing the accused considers ought to have been included in the hand-up brief, or the particulars of previous convictions of any witness on whose evidence the prosecution intends to rely in the committal proceeding.

Straight hand-up brief and election to stand trial

3.38 As part of the case direction notice, the parties may ask that the court determine the committal proceeding at the committal mention hearing without the need for witnesses to be called. The accused must indicate whether they will agree to be committed for trial. This process is referred to as a ‘straight hand-up brief’ and is the Victorian equivalent of a ‘paper committal’.

3.39 Alternatively, an accused may elect to stand trial without a committal proceeding. As soon as practicable after advising the court of this election, the accused must be brought before the court and the magistrate must commit the accused for trial in accordance with section 144 of the CPA. In practice, however, election is rarely used in place of the straight hand-up brief procedure.

Application for leave to cross-examine witnesses

3.40 If the case direction notice indicates that cross-examination of a witness or witnesses is sought, those witnesses cannot be cross-examined unless the court grants leave. An application for leave to cross-examine witnesses is determined at a committal mention hearing.

3.41 A magistrate must not grant leave to cross-examine a witness unless all of the following are satisfied:

- the accused has identified an issue to which the proposed questioning relates

- the accused has provided a reason the evidence of the witness is relevant to that issue

- cross-examination of the witness on that issue is justified.

3.42 If leave is granted, the scope of the permitted cross-examination is limited to the issues identified.

3.43 In sexual offence cases where the complainant is a child or cognitively impaired, the court cannot grant leave to cross-examine any witness during a committal proceeding. In all other sexual offence cases, the general rules relating to cross-examination of witnesses apply.

3.44 Table 2 outlines how many applications for leave to cross-examine witnesses at committal hearings were made in the last five years. This is based on number of applications, not on individual witnesses.

Table 2: Number and outcome of applications for leave to cross-examine witnesses at committal hearing[1]

| Granted[2] | Struckout[3] | Refused | Total no. of appli-cations | ||||

| No. of appli-cations | % of total no. of appli-cations | No. of appli-cations | % of total no. of appli-cations | No. of appli-cations | % of total no. of appli-cations | ||

| 2013–14 | 1,290 | 90.0% | 137 | 9.6% | 6 | 0.4% | 1433 |

| 2014–15 | 1,233 | 90.5% | 120 | 8.8% | 9 | 0.7% | 1362 |

| 2015–16 | 1,205 | 89.0% | 138 | 10.0% | 11 | 1.0% | 1354 |

| 2016–17 | 1,410 | 86.9% | 197 | 12.1% | 16 | 1.0% | 1623 |

| 2017–18 | 1,569 | 90.5% | 147 | 8.5% | 18 | 1.0% | 1734 |

[1] Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Committal Data Requested by the VLRC (24 April 2019).

[2] If a magistrate determines that one or more of the witnesses listed in the application are not to be cross-examined, but one or more other witnesses are to be cross-examined, the application is reflected in this data as granted: ibid.

[3] This involves situations where the same application has been listed twice, or when the parties have resolved the matter in a different way than indicated on their case direction notice meaning the application no longer requires determination: ibid.

Applications for summary jurisdiction

3.45 A case can be dealt with summarily in the Magistrates’ Court if the only charges remaining are either summary charges or indictable charges able to be determined summarily. This means that all other indictable charges have been withdrawn or discharged.

3.46 If this occurs, the accused can make an application for summary jurisdiction. If granted, the case is removed from the committal stream and is dealt with summarily in accordance with section 30 of the CPA. This may be for a plea hearing, or if the accused pleads not guilty to the remaining offences, for a summary hearing where the magistrate hears the evidence and determines whether the accused is guilty or not guilty.

3.47 Of committal stream cases dealt with summarily, Table 3 shows at which stage of the committal process those cases were finalised.

Table 3: Stage when committal stream cases were finalised summarily[1]

| Filing hearing[2] | Committal mention | Committal case conference[3] | Committal hearing[4] | Committal hearing (sexual offence)[5] | No. of cases finalised summ-arily | ||||||

| No. of cases | % of cases | No. of cases | % of cases | No. of cases | % of cases | No. of cases | % of cases | No. of cases | % of cases | ||

| 2013–14 | 61 | 7.0% | 464 | 53.3% | 13 | 1.5% | 310 | 35.6% | 23 | 2.6% | 871 |

| 2014–15 | 108 | 12.3% | 408 | 46.4% | 97 | 11.0% | 237 | 27.0% | 29 | 3.3% | 880 |

| 2015–16 | 86 | 10.4% | 402 | 48.7% | 59 | 7.2% | 250 | 30.3% | 28 | 3.4% | 825 |

| 2016–17 | 68 | 7.3% | 419 | 45.1% | 91 | 9.8% | 326 | 35.1% | 25 | 2.7% | 929 |

| 2017–18 | 65 | 6.5% | 433 | 43.6% | 69 | 7.0% | 413 | 41.5% | 14 | 1.4% | 994 |

[1] Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Committal Data Requested by the VLRC (24 April 2019).

[2] It is likely that cases determined summarily at filing hearing have come before the court as a result of an executed warrant to arrest where a brief has previously been served or where indictable charges are withdrawn at the filing hearing stage, leaving only summary charges: ibid.

[3] All committal stream cases must be listed for a filing hearing and a committal mention but not every case will be listed for a committal case conference or a committal hearing: ibid.

[4] See note 90 above.

[5] During the filing hearing and committal mention phase, sexual offence cases are not separated from other types of cases. Once a case is listed for committal hearing, some sexual offence cases are listed under a separate ‘Committal hearing (sexual offence)’ type, and some are listed under the general committal hearing type: Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Committal Data Requested by the VLRC (24 April 2019).

The committal hearing

3.48 At the committal hearing, a magistrate considers whether to commit the accused to stand trial based on the material in the hand-up brief, together with any other evidence given during the hearing. The court relies on the hand-up brief as the evidence in the case, along with any oral evidence.

3.49 During the hearing, the magistrate hears the evidence for the prosecution and, if the defence wishes to give evidence, for the defence.

3.50 Over the last ten years, the average duration of committal hearings was 1.47 days.

Cross-examination of witnesses at the committal hearing

3.51 If leave has been granted to cross-examine a witness, this occurs at the committal hearing. The ability to cross-examine prosecution witnesses during a committal hearing gives the accused an opportunity to explore and test the prosecution case. The transcript of this evidence, as well as any statements admitted into evidence during the committal proceeding, are called the ‘depositions’ in a case. The depositions are important if the accused is committed for trial, as they are relied upon by parties to prepare the case for trial, as well as by the higher court hearing the case.

3.52 If a witness fails to appear at the committal hearing, the magistrate may adjourn the hearing, issue a summons or warrant of arrest for the witness or continue with the committal in the absence of the witness. If the committal hearing proceeds in the absence of the witness, any statement previously made by the witness is inadmissible as evidence in the committal hearing.

The test for committal

3.53 Following a committal hearing, the magistrate must determine whether the evidence is of sufficient weight to support a conviction. If so satisfied, the magistrate must commit the accused for trial. The DPP may then file an indictment in either the Supreme or County Court, depending on the seriousness of the charge, complexity of the case and any other factors the DPP considers relevant.

3.54 If the magistrate decides the evidence is not of sufficient weight to support a conviction for any indictable offence, the accused must be discharged.

3.55 Table 4 shows the number of committal stream cases which are discharged each year.

Table 4: Outcome of committal hearings[1]

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | |

| Cases with at least one charge discharged, none committed[2] | 17 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 10 |

| Cases with some charges discharged, some committed | 91 | 57 | 54 | 61 | 57 |

[1] Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Committal Data Requested by the VLRC (24 April 2019).

[2] This includes cases that may have had charges determined summarily in the Magistrates’ Court: ibid.

3.56 By comparison, Table 5, based on data provided by the OPP, breaks down the outcomes of committal hearings over the past five years. The number of cases reported differs slightly from the number of cases provided by the Magistrates’ Court in Table 1.

Table 5: Outcome of committal hearings according to OPP[1]

| Committed[2] | Adjourned | Charges withdrawn | Summary jurisdiction granted | Discharged | Total [3] |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | |

| 2013–14 | 1081 | 50.9% | 727 | 34.3% | 52 | 2.5% | 84 | 4.0% | 26 | 1.2% | 2122 |

| 2014–15 | 926 | 47.4% | 721 | 36.9% | 46 | 2.4% | 93 | 4.8% | 18 | 0.9% | 1953 |

| 2015–16 | 929 | 50.9% | 654 | 35.8% | 30 | 1.6% | 66 | 3.6% | 25 | 1.4% | 1826 |

| 2016–17 | 1026 | 54.8% | 623 | 33.3% | 26 | 1.4% | 48 | 2.6% | 30 | 1.6% | 1872 |

| 2017–18 | 1292 | 54.2% | 745 | 31.3% | 56 | 2.3% | 116 | 4.9% | 33 | 1.4% | 2384 |

[1] Office of Public Prosecutions Victoria, Response to VLRC Request for Statistics, Victorian Law Reform Commission Committals Reference

(24 April 2019).

[2] This includes cases that were committed at the committal hearing where the accused pleaded guilty or not guilty: ibid.

[3] In addition to this total, each year approximately 135 records have been created where the outcome of the committal hearing, if any, is not known due to errors in data entry. This includes situations where no result was entered for the hearing, the hearing was booked in error, vacated, closed by the system or prosecuted by an agency other than the Office of Public Prosecutions: ibid.

Guilty pleas

3.57 If an accused enters a plea of guilty to an indictable offence at any stage during the committal proceeding, a magistrate must consider the evidence and if satisfied it is of sufficient weight to support a conviction, may commit the accused for trial in a higher court.

3.58 Alternatively, if an application for summary jurisdiction has been granted, a guilty plea may be dealt with in the Magistrates’ Court.

3.59 The Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) encourages early guilty pleas by requiring the sentencing court to have regard to whether the offender entered a guilty plea and at what stage in the proceedings this occurred.

3.60 Unlike some other jurisdictions, Victoria does not prescribe a specific discount offered to offenders for a guilty plea.

3.61 Rather, Victorian courts take an ‘instinctive synthesis’ approach to sentencing. This process requires that:

the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case. Only at the end of the process does the judge determine the sentence.

Data relating to guilty pleas

3.62 Approximately two-thirds of all cases in the committal stream currently resolve prior to committal hearing with a plea of guilty. This includes guilty pleas that are heard and determined in the higher courts, as well as guilty pleas that are heard and determined summarily.

3.63 In 2017–18:

- the OPP handled 2,995 new briefs for prosecution in the higher courts

- 91.8 per cent of prosecutions completed resulted in a guilty outcome

- 80.4 per cent of prosecutions were finalised as a guilty plea

- of the cases that involved a guilty plea, 79.4 per cent of these guilty pleas were achieved by committal.

3.64 The OPP has also provided data to the Commission which shows that of cases committed for trial following a committal hearing over the last ten years:

- 67.73 per cent of accused pleaded not guilty

- 26.55 per cent of accused pleaded guilty

- 4.56 per cent of accused entered a mixed plea

- 1.15 per cent of accused reserved their plea.

3.65 Of all cases committed to a higher court (regardless of which stage of committal proceeding this occurs), Table 6 shows the percentage of those cases that involved guilty pleas at the time of committal.

Table 5: Outcome of committal hearings according to OPP[1]

| Committed[2] | Adjourned | Charges withdrawn | Summary jurisdiction granted | Discharged | Total [3] |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | |

| 2013–14 | 1081 | 50.9% | 727 | 34.3% | 52 | 2.5% | 84 | 4.0% | 26 | 1.2% | 2122 |

| 2014–15 | 926 | 47.4% | 721 | 36.9% | 46 | 2.4% | 93 | 4.8% | 18 | 0.9% | 1953 |

| 2015–16 | 929 | 50.9% | 654 | 35.8% | 30 | 1.6% | 66 | 3.6% | 25 | 1.4% | 1826 |

| 2016–17 | 1026 | 54.8% | 623 | 33.3% | 26 | 1.4% | 48 | 2.6% | 30 | 1.6% | 1872 |

| 2017–18 | 1292 | 54.2% | 745 | 31.3% | 56 | 2.3% | 116 | 4.9% | 33 | 1.4% | 2384 |

[1] Office of Public Prosecutions Victoria, Response to VLRC Request for Statistics, Victorian Law Reform Commission Committals Reference

(24 April 2019).

[2] This includes cases that were committed at the committal hearing where the accused pleaded guilty or not guilty: ibid.

[3] In addition to this total, each year approximately 135 records have been created where the outcome of the committal hearing, if any, is not known due to errors in data entry. This includes situations where no result was entered for the hearing, the hearing was booked in error, vacated, closed by the system or prosecuted by an agency other than the Office of Public Prosecutions: ibid.

3.66 In 2015, the Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council examined the timing of guilty pleas in higher courts. Of cases involving a guilty plea, Table 7 shows the point at which offenders pleaded guilty. While this data is not current, it demonstrates when a majority of pleas are entered and how many occur late in the process.

Table 7: Timing of guilty pleas for all proven cases in the County and Supreme Courts 2009–10 to 2013–14[1]

| Court event | Number of cases | % of cases[2] |

| Committal stage (Magistrates’ Court) | 5,546 | 55.4% |

| Callover/case conference (in higher court) | 128 | 1.3% |

| At higher court directions hearing | 230 | 2.3% |

| After higher court directions hearing | 1,421 | 14.2% |

| Door of higher court | 1,307 | 13.1% |

| During higher court trial | 268 | 2.7% |

| Found guilty at trial | 1,095 | 11.0% |

[1] Ibid [2.36].

[2] The total number of proven cases in the County and Supreme Courts between 2009–10 and 2013–14 was 9,995: ibid [2.36].

Commonwealth offences

3.67 Victorian courts have jurisdiction to hear matters relating to Commonwealth criminal offences. Victoria’s criminal procedure rules apply in these instances.

3.68 Commonwealth offences are prosecuted by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (Commonwealth DPP). Prosecutorial decisions are governed by the Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth.

3.69 If the court determines the evidence is of sufficient weight to support a conviction in relation to a Commonwealth offence, the accused may be committed for trial in either the Federal Court or a Victorian higher court. Before committing a matter for trial the magistrate must invite the Commonwealth DPP to suggest the appropriate court in which the matter should be heard.

Committal proceedings in the Children’s Court

3.70 The Criminal Division of the Children’s Court has jurisdiction to both:

- hear and determine all charges against children for summary offences

- hear and determine summarily all charges against children for indictable offences, other than categorised offences such as murder, attempted murder and manslaughter.

3.71 In 2018, amendments to the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic) (CYFA) created two categories of offence:

- Category A serious youth offences—if an accused child is aged 16 or over at the time of the offence, it is presumed that these cases will be determined in a higher court.

- Category B serious youth offences—if an accused child is aged 16 or over at the time of the offence, the Children’s Court must consider whether the charge is suitable to be heard and determined summarily before proceeding.

3.72 Where an offence is too serious to be dealt with in the Children’s Court, or it determines it unsuitable to do so, the case is ‘uplifted’ to a higher court. Before being transferred, committal proceedings are conducted in the Children’s Court and follow the procedure prescribed in the CPA.

3.73 Prior to the 2018 amendments, the only offences that could not be dealt with by the Children’s Court were six death-related offences. Applications for uplift could be made in other serious matters involving an accused child but it was uncommon for the Court to find that a charge should be dealt with in a superior court.

3.74 Table 8 captures information about committal cases in the Children’s Court.

Table 8: Committal cases in the Children’s Court[1]

| 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018-19[2] | |

| Committal stream cases initiated[3] | 9 | 15 | 13 | 22 | 45[4] |

| Cases committed without a committal hearing[5] | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Committal hearings | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Cases discharged following committal hearing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Matters dealt with summarily | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 19 |

| Other[6] | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

[1] Response to Request for Children’s Court Data Email from Children’s Court of Victoria to Victorian Law Reform Commission, 16 May 2019.

[2] The figure in this column reflects data as at 10 May 2019, but more cases are likely to have been initiated prior to 1 July 2019: ibid.

[3] When considering this data, it is important to remember that while a matter may be initiated in a certain reporting period, it may not necessarily be finalised in that same period: ibid.

[4] Of these 45 cases, four involved a death-related offence, 39 involved a Category A serious youth offence and the two remaining matters were considered unsuitable for summary jurisdiction: ibid.

[5] This involves cases where pleas of guilty or not guilty (straight hand-up brief) were entered: ibid.

[6] The Children’s Court notes that further analysis is needed to explain what cases fall within this category: ibid.

3.75 This shows that following the 2018 CYFA amendments, there has been a two-fold increase in the number of initiations in the Children’s Court committal stream.

Direct indictments

3.76 The DPP has the power to directly indict an accused person for trial. This power rests solely with the DPP and is not subject to judicial review.

3.77 The DPP can directly indict an accused after a magistrate has discharged that accused following a committal hearing, but to do so involves the DPP making a ‘special decision’. The DPP can only make a special decision after having obtained the advice of the Director’s Committee.

3.78 The Director’s Policy states that a direct indictment can be filed after an accused has been discharged at committal only if, in the view of the Director’s Committee, all of the following apply:

- the magistrate made an error in discharging the accused

- the DPP’s criteria governing the decision to prosecute are satisfied

- there has not been unreasonable delay between the accused being discharged and the decision to directly indict.

3.79 The Director’s Policy also provides that a direct indictment may be filed where no committal has been held, if:

- there are strong grounds justifying a trial without a committal

- a trial without a committal would not be unfair to the accused.

3.80 Table 9 below shows how many direct indictments were filed by the DPP over the last five years. The OPP does not have specific data about how many were filed following discharge by a magistrate at committal.

Table 9: Direct indictments filed by the DPP[1]

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | |

| Direct indictments | 21 | 15 | 11 | 16 | 19 |

[1] Ibid.

Pre-trial witness examination

3.81 Committal hearings are not the only occasion prior to trial when witnesses may be required to give evidence. Different pre-trial mechanisms for cross-examination of witnesses apply to different types of cases and in a variety of circumstances.

3.82 This section outlines the different ways a witness can be required to give evidence prior

to trial.

General (non-sexual offence) cases

Section 198B

3.83 Codifying hearings previously known as ‘Basha hearings’, section 198B of the CPA allows an accused person to apply for an order permitting cross-examination of a witness. This cannot be granted unless the court is satisfied that it is necessary to do so in order to avoid a serious risk that the trial would be unfair.

3.84 An order under section 198B can be made both before and during a trial. If made during trial, cross-examination takes place in the absence of the jury.

3.85 The same restrictions that apply when granting leave to cross-examine a witness during a committal hearing apply when deciding whether to make an order under section 198B.

Section 198

3.86 If a witness is not available at the time set for the trial, an order may be granted for their examination to take place prior to trial. This type of order must not be made unless the court is satisfied it is in the interests of justice to do so.

Voir dire

3.87 A ‘voir dire’ is a ‘hearing in which a court determines questions of fact and law after hearing evidence from witnesses’.

3.88 The voir dire process is based in common law.

3.89 It is rare that a witness who has given evidence at a committal hearing will also be required to give evidence at a voir dire. Evidence given during a voir dire does not form part of the evidence in the trial, but is instead given to allow the judge to determine a question of law such as whether the evidence of a witness is admissible, or whether it should be rejected on discretionary grounds.

Sexual offences

3.90 When applying the sections of the CPA which deal with witnesses in sexual offence cases, courts are required to have regard to the fact that:

- there is a high incidence of sexual violence within society

- sexual offences are significantly underreported

- a significant number of sexual offences are committed against women, children and other vulnerable persons including persons with a cognitive impairment

- offenders are commonly known to their victims

- sexual offences often occur in circumstances where there is unlikely to be any physical sign of an offence having occurred.

Section 198A

3.91 Witnesses in a sexual offence case involving a complainant who is either under the age of 18 or cognitively impaired cannot be ordered to be cross-examined during a committal hearing. Section 198A, however, allows an accused to make an application to cross-examine a witness other than the complainant at any time except during a trial.

3.92 An application under section 198A must state:

- each issue for which leave to cross-examine is sought

- the reason the evidence of the witness is relevant to the issue

- the reason cross-examination of the person on the issue is justified.

Special hearings

3.93 If a complainant in a sexual offence case is under the age of 18 or has a cognitive impairment, the whole of their evidence (including cross-examination) must be given either before or during the trial at a ‘special hearing’. If held during a trial, the jury must be present during the special hearing.

3.94 If the special hearing takes place prior to the trial, the audio-visual recording of the special hearing constitutes the complainant’s evidence at trial and is played for the jury.

3.95 During the special hearing, the accused cannot be in the same room as the complainant but is entitled to see and hear the evidence being taken.

3.96 Once evidence is given at a special hearing, the court can only grant leave to cross-examine or re-examine a witness in limited circumstances.

Recorded evidence-in-chief

3.97 In cases involving sexual offences, family violence or assault, a recording of a witness answering questions put to them by the informant (or by another person prescribed in the CPA) can be played during a trial in place of that witness giving evidence-in-chief.

3.98 This only applies to witnesses who are either under the age of 18 or who have a cognitive impairment.

Other protections for witnesses

3.99 Throughout a criminal proceeding, there are a number of other procedures and rules protecting witnesses in sexual offence (and other) cases. They include:

- a prohibition on questions that relate to a complainant’s chastity

- a restriction on questioning that relates to a complainant’s prior sexual history

- a prohibition on a protected witness in a sexual offence case or a case involving family violence, from being personally cross-examined by the accused

- provision for alternative arrangements for giving evidence for witnesses in cases involving sexual offences and family violence, such as giving evidence by CCTV, from behind a screen or in the presence of a support person.

Intermediaries for witnesses and ground rules hearings

3.100 Following recommendations made by the Commission in 2016, an intermediary scheme was established. Appointed by the court in certain cases, an intermediary’s role is to facilitate communication between witnesses under the age of 18 or with a cognitive impairment (‘vulnerable witnesses’), and the court. The CPA allows intermediaries to be appointed for vulnerable witnesses at any stage of a criminal proceeding, including committal hearings.

3.101 As an officer of the court, an intermediary has a duty to act impartially when helping a witness to communicate their evidence.

3.102 A ground rules hearing can be ordered whether or not an intermediary has been appointed. A ground rules hearing involves a discussion between the parties, the court and any intermediary appointed about how a vulnerable witness’s evidence will be taken. This may involve the court making directions about particular issues, such as how and for how long a witness is to be questioned and the use of aids to help communicate a question or an answer.

3.103 Ground rules hearings can only be held in cases involving charges for a sexual offence, charges that arise in circumstances of family violence, or charges involving an assault on, or injury or a threat of injury to, a person.

3.104 The Intermediary Pilot Program is in operation until 30 June 2020, and limits the use of intermediaries and ground rules hearings to:

- complainants in sexual offence cases who are under the age of 18 or cognitively impaired

- witnesses in homicide matters who are under the age of 18 or cognitively impaired.

3.105 The operation of the Intermediary Pilot Program, including the process through which an intermediary is appointed, is outlined in the County Court’s ‘Multi-Jurisdictional Court Guide for the Intermediary Pilot Program’. This is supplemented by the Magistrates’ Court Practice Direction 6 of 2018.

Time limits

3.106 There are a variety of time limits that the parties must adhere to in committal proceedings, designed to assist with the court’s management of cases. For example, a committal mention hearing must be held within six months of the commencement of the proceeding, unless it is in the interests of justice to extend this time, and parties are required to engage in discussions to explore resolution of the case at least 14 days prior to a committal mention hearing.

3.107 Another important timeframe, which is fixed by a magistrate at filing hearing, is the date by which the informant must serve the hand-up brief on the accused and prosecution. In most cases, this must be at least 42 days prior to the committal mention.

3.108 Table 10 shows the median number of days it takes for a case to be committed to a higher court when this happens at a committal hearing.

Table 10: Median time (days) for a case to be committed at committal hearing[1]

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | |

| Filing hearing to committal hearing[2] | 185 | 193 | 214 | 232 | 228 |

| Filing hearing to committal hearing (sexual offence) | 153 | 151 | 194 | 208 | 193* |

[1] Ibid.

[2] Some sexual offence committal hearings may be included in this data: ibid.

3.109 By comparison, Table 11 shows the median number of days it takes for a case to be committed to a higher court when this happens at either a committal mention or committal case conference.

Table 11: Median time (days) for a case to be committed at committal mention or case conference[1]

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | |

| Filing hearing to committal mention | 91 | 97 | 98 | 104 | 107 |

| Filing hearing to committal case conference | 105 | 85 | 84 | 84 | 84 |

[1] Ibid.

3.110 In Tables 10 and 11, cases where one or more warrants to arrest were issued were removed from the dataset to avoid inflating the median number of days.

3.111 The overall time frame to complete the prosecution of an indictable case was an average of 17.6 months in 2016–17 and 15.5 months in 2017–18. The five year average to 2017–18 is 19.9 months.

3.112 Table 12 shows the current backlog in Victorian courts, expressed as a percentage of the total pending caseload in each court. Cases in which a warrant of arrest was issued are not included in this data. In the Magistrates’ Court, the figures include all summary as well as committal stream cases. In the Supreme and County Courts, the figures exclude appeal cases.

Table 12: Backlog in Victorian courts (as at 30 June), 2017–18[1]

| Supreme Court | County Court | Magistrates’ Court[2] | Children’s Court | |

| Cases > 6 months (%) | 27.9% | 16.6% | ||

| Cases > 12 months (%) | 25.0% | 19.5% | 10.3% | 4.2% |

| Cases > 24 months (%) | 8.1% | 4.1% |

[1] Ibid.

[2] Ibid Table 7A.17(i). The Australian Productivity Commission explains that the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria data is unaudited and subject to revision. A review of data capture and extraction processes has been foreshadowed.

3.113 Table 13 shows the time taken to finalise a case from its date of commencement, expressed as a percentage of the total number of finalised cases in each court. The data reflects all pending cases in each court (excluding appeal cases), not just pending committal stream cases.

Table 13: Time taken to finalise cases in Victorian courts, 2017–18[1]

| Supreme Court | County Court | Magistrates’ Court[2] | Children’s Court | |

| Cases finalised <= 6 months (%) | 74.7% | 88.1% | ||

| Cases finalised <= 12 months (%) | 69.5% | 82.1% | 90.7% | 96.8% |

| Cases finalised <= 24 months (%) | 92.7% | 97.6% |

[1] Ibid Table 7A.19.

[2] Ibid Table 7A.19(d). The Australian Productivity Commission explains that the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria data is unaudited and subject to revision. A review of data capture and extraction processes has been foreshadowed.

Access to legal aid

3.114 The Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) recognises that an accused person has a right ‘to have legal aid provided if the interests of justice require it’.

3.115 Victoria Legal Aid’s (VLA) guidelines state that legal aid will be provided for representation during committal proceedings if either:

- the accused has been charged with homicide (including culpable driving and attempted murder) or

- there is a real issue of consent or identification.

3.116 In all other cases, legal aid will be provided if the available material suggests there is a ‘strong likelihood’ that a benefit will result from representation. Examples of ‘benefit’ include:

- the charge that the accused person faces will be dealt with summarily

- a committal hearing is likely to result in an early plea

- a committal hearing will lead to a significant reduction in the length of any later trial or plea

- the person will be discharged at the committal.

3.117 A separate grant of aid must be sought if a case proceeds to a committal hearing. For aid to be granted for a committal hearing, the same eligibility requirements apply but the standard for satisfying them is higher.

|

|