Review of the Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997: Consultation Paper

5. Defence of mental impairment

Introduction

5.1 This chapter examines the defence of mental impairment under the Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) (CMIA). It briefly explores the history of the defence prior to the CMIA—the ‘insanity’ defence. It sets out the current law and procedure for the defence of mental impairment under the CMIA. It raises the issues regarding the mental impairment defence that have been specified in the terms of reference and seeks to identify whether there are any issues in relation to the way the law operates.

5.2 Throughout the chapter, the Commission asks a number of questions about possible changes to the law and if so, what changes to recommend.

5.3 The terms of reference ask the Commission to consider a number of particular issues with regard to the mental impairment defence. These are, whether:

• the CMIA should define ‘mental impairment’ and if so, how it should be defined, and

• legislative clarification is required on how the law should provide for the jury to approach the elements of an offence, and any defences or exceptions when the defence of mental impairment is in issue.

5.4 The issue, also specified in the terms of reference, of whether there should be expansion of the orders available in the Magistrates’ Court after a finding of not guilty because of mental impairment is discussed in Chapter 6.

5.5 For an accused person to be criminally responsible for committing an offence, it must be demonstrated that the person committed both the physical and mental elements of that offence. Criminal responsibility requires ‘both a criminal act, and a criminal or guilty mind accompanying that act’.[1] For example, for a person to be found guilty of the offence of murder, it must be proven that the person:

• engaged in conduct that caused the death of another person, such as firing a gun (the physical element or actus reus), and

• intended to kill that person or cause serious injury or knew that their conduct was likely to cause the death of that person (the mental element or mens rea).

5.6 The term mens rea encompasses two aspects relating to an accused person’s mental state. One aspect is a technical issue regarding ‘the fault elements associated with a particular offence, that is, the particular mental ingredients which the prosecution must prove to secure a conviction for a particular offence’.[2] The most common fault elements are intention, knowledge and recklessness.

5.7 The other aspect is the extent to which the accused person should be held responsible for their mental state, that is whether they had the capacity to understand their thoughts and actions and whether they knew they were morally wrong. If it arises, the question of mental capacity must be dealt with before the question of whether the accused person formed the relevant intent.

5.8 The law has long recognised that a person should not be held criminally responsible if at the time of committing an offence, the person lacked the mental capacity to commit the offence because of a mental impairment.

5.9 People found guilty of committing offences are sentenced for a number of reasons. These include punishing the offender in proportion to the offence committed, protection of society from harm and as a deterrent to others from committing offences.[3]

5.10 Punishment is not an appropriate response to people who are found not criminally responsible for their actions. This is because they cannot be deterred or influenced by the prospect of being punished or are unable to understand the legal ramifications of the actions.[4] This rationale for the defence of mental impairment ‘remains as valid today as it did when it first evolved’.[5]

5.11 The defence of mental impairment is therefore grounded in two important principles:

• a mental impairment may act as an excuse from criminal responsibility

• the community must be protected from people who, as a result of a mental impairment, are a risk to themselves or others.[6]

The law prior to the CMIA—the ‘insanity defence’

5.12 As discussed in Chapter 2, the principles underlying the insanity defence have been in existence for centuries. However, the insanity defence was not developed as a legal doctrine until the early 1800s. The legal defence was formulated as a result of two English cases: R v Hadfield[7] and Daniel M’Naghten’s Case.[8]

5.13 In the case of R v Hadfield, James Hadfield, while suffering from delusions, attempted to shoot King George III. Hadfield was found not guilty by reason of insanity and held in custody. However, at the time there was no authority to detain people found not guilty by reason of insanity. This case prompted the introduction of the Criminal Lunatics Act 1800, that allowed for people acquitted on the grounds of insanity to be kept in custody at the King’s pleasure. This legislation was later adopted in Australia and formed the basis for the Governor’s pleasure regime. Under the Governor’s pleasure regime, the detention of a person found not fit to plead or not guilty on the ground of insanity was authorised by sections 420(1) and 393(1) of the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic).

5.14 In Daniel M’Naghten’s Case, Daniel M’Naghten was accused of the murder of Edward Drummond, who was the Secretary to the English Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel. M’Naghten was under the delusion that the Tory party was persecuting him and that his life was in danger and mistakenly shot Drummond, thinking he was the prime minister. M’Naghten was acquitted on the grounds of insanity. However, there was a public outcry at the verdict and the court (the House of Lords) was asked to provide an explanation of the operation of the insanity defence.

5.15 In setting out the requirements for establishing the common law defence of insanity, the court in M’Naghten said:

jurors ought to be told that in all cases every man is to be presumed to be sane, and to possess a sufficient degree of reason to be responsible for his crimes, until the contrary be proved to their satisfaction; and that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of committing the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.[9]

5.16 In Victoria, these requirements known as the ‘M’Naghten rules’ provided the basis for the common law defence of insanity that existed under the Governor’s pleasure regime. These rules provide the ‘template for the defence of insanity in the criminal law of numerous jurisdictions’.[10]

The defence of mental impairment under the CMIA

Law

5.17 The common law defence of insanity is explicitly abolished by section 25 of the CMIA and replaced with the statutory defence of mental impairment.[11]

5.18 However, the concept of mental impairment and the statutory test for the defence of mental impairment under the CMIA is the same as it was under the common law defence of insanity. In the second reading speech for the Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Bill, the Attorney-General explained:

The term ‘insanity’ has been replaced by the term ‘mental impairment’ because the former term is antiquated and carries [a] historical stigma. However, it is important to note that the bill does not alter the existing criminal law in relation to determining criminal responsibility … The bill makes it clear that the new defence of mental impairment has the same meaning as the defence formerly known as the defence of insanity and is to be interpreted accordingly.[12]

5.19 This position was affirmed in the case of R v Sebalj where it was held that ‘the term “mental impairment” should not be construed as changing the common law but construed as referring to the concept of “a disease of the mind” used in the common law defence of insanity’.[13] The M’Naghten elements of the defence were added to the statutory defence without any alteration.[14]

5.20 Thus, the changes made by the CMIA to the defence of mental impairment were largely changes in terminology and not expected to affect the scope of the defence in practice.[15]

5.21 The defence of mental impairment is defined in section 20 of the CMIA. The defence is established if at the time of engaging in conduct constituting the offence, the person was suffering from a mental impairment that had the effect that:

• the person did not know the nature and quality of the conduct, or

• the person did not know that the conduct was wrong.

5.22 The CMIA provides that a person will not know their conduct was wrong where they ‘could not reason with a moderate degree of sense and composure about whether the conduct, as perceived by reasonable people, was wrong’.[16]

5.23 In summary, the requirements to establish the defence of mental impairment under the CMIA are that a person has a mental impairment, characterised as a ‘disease of the mind’, and that condition had at least one of two effects:

• the person did not know the nature and quality of the conduct, or

• the person was not capable of reasoning that the conduct was, or could reasonably be perceived as, wrong.

Process

5.24 The mental impairment defence under the CMIA operates at all court levels. Different processes are followed depending on the court level.

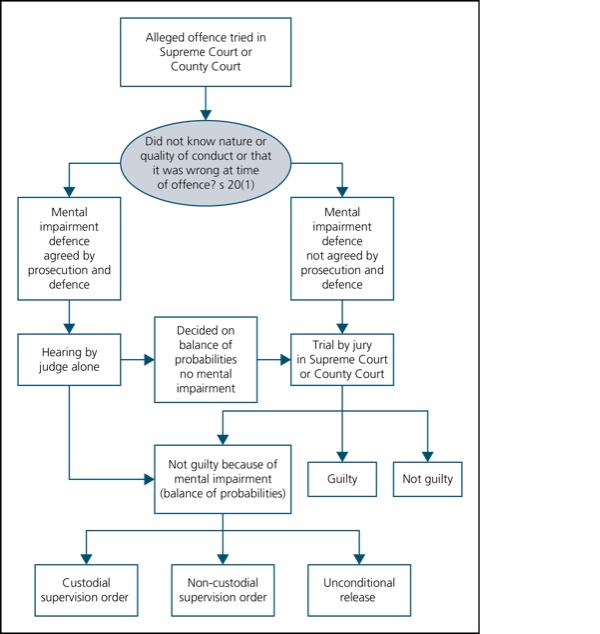

5.25 Figure 2 shows the key stages of the process for determining and establishing the defence of mental impairment in the Supreme Court and County Court.

5.26 When an accused person appears in any court, they are presumed not to be suffering from a mental impairment.[17] This is the case for all criminal proceedings, regardless of whether the defence of mental impairment has previously been raised by an accused person in another matter.

5.27 The defence of mental impairment may be raised by the prosecution or the defence at any time during the trial.[18] It is up to the party raising the defence to rebut the presumption that the accused person is not suffering from a mental impairment.[19]

5.28 The question of whether an accused person was suffering from a mental impairment at the time the offence was committed is a question of fact to be determined by a jury on the balance of probabilities.[20]

5.29 Where the prosecution and defence both agree that the proposed evidence establishes the defence of mental impairment, the trial judge may determine whether or not the accused person is not guilty because of mental impairment. If the trial judge is satisfied that the evidence establishes the defence of mental impairment, the judge may direct that a verdict of not guilty because of mental impairment be recorded.[21] If the trial judge is not satisfied that the evidence establishes the defence of mental impairment, the judge must direct that question be determined by a jury.[22] This process known as ‘consent mental impairment’ dispenses with the need to empanel a jury to determine whether the accused person was suffering from a mental impairment.

5.30 If the defence of mental impairment is raised in the course of a trial, there are three possible outcomes. The accused person may be found guilty, not guilty, or not guilty because of mental impairment. If the accused person is found not guilty because of mental impairment, they may be placed on a supervision order (custodial or non-custodial) or may be unconditionally discharged.[23]

5.31 In the Magistrates’ Court, the magistrate must discharge a person who is found not guilty because of mental impairment.[24] The consent mental impairment process is not available in the Magistrates’ Court.

Figure 2: Defence of mental impairment under the CMIA in the Supreme Court and County Court

Other mental state defences

5.32 The Commission’s reference is on the defence of mental impairment under the CMIA. However, an important context to the defence is the other mental state defences available in Victoria.

5.33 A person accused of committing an offence may claim a defence to either justify their actions or to excuse them, partially or wholly, from criminal responsibility. The difference between a justification or an excuse can be distinguished as follows:

defences ‘justifying’ a crime focus on the accused’s act whereas those ‘excusing’ a person from criminal responsibility are generally viewed as concentrating on the accused’s personal characteristics.[25]

5.34 A defence may be a complete defence or a partial defence. A complete defence (for example automatism) operates to provide the accused person with an acquittal whereas a partial defence (such as infanticide) operates to reduce murder to manslaughter.[26] Victorian law includes a number of other defences categorised as mental state defences. Included in this category are mental impairment, automatism, intoxication and infanticide. These are outlined in Table 2 below.

5.35 The Commission’s Defences to Homicide: Final Report reviewed mental state defences available in Victoria and recommended that the defences of automatism and infanticide remain unchanged.[27] Changes were recommended to the defence of intoxication that are reflected in the current legislation.[28]

5.36 Other jurisdictions in Australia have largely the same mental state defences. A number of jurisdictions (Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Northern Territory and Queensland) also have the defence of diminished responsibility. In these jurisdictions, diminished responsibility, like infanticide, is a partial defence to homicide.

5.37 There are three common elements across Australian jurisdictions that must be proven on the balance of probabilities to establish the partial defence of diminished responsibility:

• the accused person must have been suffering from an abnormality of mind

• the abnormality of mind must have arisen from a specified cause, and

• the abnormality of mind must have substantially impaired the accused person’s mental responsibility for the killing.[29]

5.38 Diminished responsibility is not a defence in Victorian law. The Commission’s Defences to Homicide: Final Report recommended that diminished responsibility should not be introduced in Victoria and that a mental disorder should instead continue to have a mitigating effect that is taken into account in sentencing.[30]

Table 2: Other mental state defences in Victoria

|

Defence |

Type of defence |

Requirements |

Outcome |

|

Automatism |

Full defence |

Involuntary conduct resulting from some form of impaired consciousness. The defence may raise automatism by alleging that the elements of the offence have not been proved because the actions of the accused person were not voluntary. |

Acquitted on the grounds of automatism. In certain circumstances, the accused person may raise the defence of mental impairment and be subject to supervision or unconditionally released. |

|

Intoxication |

Factor in deciding whether an element of a crime has been proven. |

Intoxication can be used as a defence where the intoxication was not voluntary or intentional. |

If intoxication negates an element of an offence, the outcome will be acquittal. |

|

Infanticide |

Partial defence Operates as an offence and defence in New South Wales and Victoria. |

Where a woman carries out conduct that causes the death of her child in circumstances that would constitute murder and, at the time of carrying out the conduct, the balance of her mind was disturbed because of her not having fully recovered from the effect of giving birth to that child within the preceding two years, or a disorder consequent on her giving birth to that child within the preceding two years.a |

If the partial defence is successful, the woman will be found guilty of infanticide, and not of murder, and liable to level six imprisonment (five years maximum).b |

a Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) s 6(1).

b Ibid.

Establishing the defence of mental impairment

5.39 This section will outline how the defence of mental impairment is established. In doing so, it will consider a number of issues including:

• how ‘disease of the mind’ has been interpreted by the courts in determining criminal responsibility

• whether ‘mental impairment’ should be defined and if so, how it should be defined

• the application of the defence of mental impairment and the test for determining whether a person qualifies for the defence.

The meaning of ‘mental impairment’

5.40 The term ‘mental impairment’ is not defined under the CMIA. The terms of reference ask whether the CMIA should define ‘mental impairment’ and if so, how this term should be defined.

Current meaning under the CMIA—‘disease of the mind’

5.41 The common law is relied upon in determining what constitutes a mental impairment, which states that a person must be ‘labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind’[31] in order for the defence of mental impairment to be established.

5.42 A ‘disease of the mind’ has been held to be synonymous with a ‘mental impairment’.[32]

5.43 The question of what constitutes a ‘mental impairment’ is a legal rather than medical one[33] and this legal construct is ‘often difficult to reconcile within medical and public paradigms of mental illness and justice’.[34]

5.44 There has been much debate about which mental conditions constitute a disease of the mind and it is argued ‘[l]egal definitions of what constitutes a mental condition in the insanity defence are generally unclear and variable’.[35]

5.45 In order for the defence of mental impairment to be established, the actions of the accused person must be caused by a ‘defect of reason’, that results from ‘an underlying pathological infirmity of the mind, be it of long or short duration and be it permanent or temporary, which can be properly termed mental illness, as distinct from the reaction of a healthy mind to extraordinary external stimuli’.[36]

5.46 While mental illness clearly falls within the scope of the defence of mental impairment, it remains unclear whether other conditions such as cognitive impairment, intellectual disability, drug induced psychosis or severe personality disorder constitute a mental impairment.

5.47 A ‘disease of the mind’ does not require a physical deterioration in brain cells or changes to the structure of fibres and tissues as found in other medical conditions, but it does require that ‘the functions of the understanding are through some cause, whether understandable or not, thrown into derangement or disorder’.[37]

5.48 While it is emphasised that a mental impairment may arise from a temporary or long standing disorder, it is not constituted by ‘[m]ere excitability of a normal man, passion, even stupidity, obtuseness, lack of self-control, and impulsiveness’.[38]

5.49 Examples of conditions that have been stated to be diseases of the mind include:[39]

• major mental illnesses such as schizophrenia[40]

• brain injuries, tumours or disorders[41]

• physical diseases that affect the soundness of mental faculties, such as cerebral arteriosclerosis.[42]

5.50 Examples of conditions that have been stated not to be diseases of the mind include:[43]

• concussion from a blow to the head[44]

• drug-induced psychosis.[45]

5.51 It is unclear if cases of dissociation and epilepsy constitute a mental impairment.[46] Hyperglycaemia has been found to constitute a mental impairment[47] while hypoglycaemia has been held not to constitute a mental impairment.[48]

Should ‘mental impairment’ be defined in the CMIA?

5.52 The question of whether a statutory definition of mental impairment is required has been previously considered in other reviews.

5.53 Victoria remains one of the few Australian jurisdictions that does not provide a definition of mental impairment. Appendix B outlines how mental impairment is defined in Australian jurisdictions along with New Zealand, Scotland, the United Kingdom and Canada. Apart from New South Wales, all other Australian jurisdictions provide some form of a definition of mental impairment.

5.54 The New South Wales Law Reform Commission is currently reviewing the need for a definition as part of a broader project on people with cognitive and mental health impairments in the criminal justice system.[49] The New South Wales Law Reform Commission transmitted a report on criminal responsibility and consequences to the New South Wales Attorney-General on 7 May 2013.

5.55 The need for legal certainty around what constitutes a mental impairment is a compelling reason for developing a statutory definition. Those supporting the development of a statutory definition of mental impairment argue that it is unclear which mental conditions fall within the scope of the defence, particularly in relation to intellectual disability and cognitive impairment. Inconsistencies in the application of the term have led to calls for certainty in the law:

given the onerous nature of both criminal sanctions and the dispositional regime attendant upon a finding of insanity, certainty in the law must be established. It is incumbent on the criminal law to ensure that a consistent set of rules determine when people are and are not criminally responsible.[50]

5.56 Prior to the introduction of the CMIA, the Victorian Parliamentary Community Development Committee in its review of the Governor’s pleasure regime recommended introducing a statutory definition of mental impairment.[51]

5.57 While appreciating the need for flexibility in interpreting the term ‘mental impairment’, the Community Development Committee acknowledged that ‘both the category of people likely to plead the insanity defence, their families and their legal counsel should be provided with some statutory guidance as to what the term means’ and recommended a statutory definition be developed.[52]

5.58 The issue was re-examined in the Commission’s defences to homicide report. In that report, the Commission recommended retaining the current defence of mental impairment without including a statutory definition of mental impairment.

5.59 The Commission’s report argued that difficulties in adequately defining the term ‘mental impairment’ would mean that any definition would be equally problematic and subject to criticism as having no definition at all.[53]

5.60 The complexities in developing a definition of mental impairment were highlighted by McSherry and Naylor:

One of the initial difficulties with this criterion [for the defence of mental impairment] is that a clear definition of mental impairment, or even mental illness, has eluded members of the medical as well as the legal professions.[54]

5.61 Consultations undertaken as part of the Commission’s defences to homicide report indicated that the defence was working well in practice and leaving the term undefined would ensure flexibility in its application.[55] The review instead recommended that a provision be added to the CMIA that specifies what the term ‘mental impairment’ includes but is not limited to the common law notion of ‘disease of the mind’.[56]

5.62 In March 2013, the Victorian Parliament Law Reform Committee released a report, Inquiry into Access to and Interaction with the Justice System by People with an Intellectual Disability and their Families and Carers, that acknowledged there is ambiguity in the meaning of the term ‘mental impairment’ and recommended that a statutory definition be developed.

Questions

29 How does the defence of mental impairment work in practice with ‘mental impairment’ undefined?

30 Should ‘mental impairment’ be defined under the CMIA?

31 What are the advantages or disadvantages of including a definition of mental impairment in the CMIA?

If mental impairment is defined, how should it be defined?

5.63 Previous reviews have identified that developing a definition of what constitutes a mental impairment can be problematic. A number of different options have been proposed for defining mental impairment, including:

• categories of impairments (for example, listing conditions that are included such as mental illness, intellectual disability and cognitive impairments)

• diagnostic criteria (such as those in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)

• operational definition (for example by linking the impairment to its effect on the person’s ability to understand, know or control their behaviour).

5.64 Other Australian jurisdictions with statutory definitions of mental impairment employ a mixture of categorical and operational definitions. Appendix B provides details of the different approaches.

5.65 The Commonwealth definition of mental impairment includes senility, intellectual disability, mental illness, brain damage and severe personality disorder.[57] South Australia, Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory have substantially adopted this definition. The Northern Territory includes the category of involuntary intoxication and South Australia excludes intoxication.[58]

5.66 Queensland legislation provides that a mental impairment is a ‘mental disease’ or ‘natural mental infirmity’ while Tasmanian legislation outlines that a ‘mental disease’ includes ‘natural imbecility’.[59]

5.67 The Community Development Committee considered whether Victoria should align itself with the Commonwealth Code by incorporating a volitional element (that is, an element about the person’s ability to control their actions). However, the Community Development Committee was unable to resolve competing arguments and stated the area required further consideration.[60] It therefore recommended development of a statutory definition of ‘mental impairment’ that includes mental illness, intellectual disability, acquired brain injury (including senility) and severe personality disorder.[61]

5.68 Most Australian states provide broad definitions of mental impairment that incorporate a volitional element by linking the mental impairment to the person’s ability to understand, control their actions or know that they ought not to do the act or make the omission.

5.69 In 1990, the Law Reform Commission of Victoria’s report Mental Malfunction and Criminal Responsibility recommended that ‘mental impairment should be defined so as to include mental illness, personality disorder, intellectual disability, senility and brain damage’.[62]

5.70 The Law Reform Committee’s report recommended that mental impairment ‘encompass mental illness, intellectual disability, acquired brain injuries and severe personality disorders’.[63] The report argued that a definition would ensure Victoria is consistent with legislation in other Australian jurisdictions that ‘expressly recognise intellectual disability and some other cognitive impairments such as ABIs [acquired brain injuries] and senility as conditions that may qualify a defendant for the defence’.[64]

5.71 The use of diagnostic criteria to provide a definition of mental impairment was considered in the Commission’s Defences to Homicide report. The Commission identified concerns raised by both medical and legal practitioners that mental impairment does not accurately reflect current thinking on mental illness.[65] The Commission concluded, however, that the use of a diagnostic tool, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) would be inappropriate as knowledge about mental illness is constantly changing and these tools are not designed to be used in a legal context.[66]

5.72 Others also argue that a statutory definition based on diagnostic criteria would be inappropriate and inflexible, and that:

By ensuring that the legal expression is not tied down to diagnostic criteria courts and relevant bodies remain free to facilitate the execution of this normative task undertaken as part of the disease of the mind enquiry.[67]

Questions

32 If mental impairment is to be defined in the CMIA, how should it be defined?

33 What conditions should constitute a ‘mental impairment’? Are there any conditions currently not within the scope of a mental impairment defence that should be included? If so, what are these conditions?

34 If a statutory definition of mental impairment is not required, what other measures could be taken to ensure the term is applied appropriately, consistently and fairly?

The test for establishing the defence of mental impairment

Knowledge about the nature and quality of the act

5.73 The requirement that the accused person not know the nature and quality of the act refers only to the ‘physical character of the act’.[68]

5.74 The High Court has described this requirement as a person’s ‘capacity to comprehend the significance of the act of killing and of the acts by means of which it was done’.[69]

5.75 In simple terms, a person will not know the nature and quality of their conduct if because of a mental impairment they do not know ‘the physical thing [they were] doing and its consequences’.[70] This statement implies that the knowledge of the accused person relates to more than just the physical act:

In R v Porter, the common-law requirement of an accused’s lack of knowledge of the nature and quality of an act has been interpreted as consisting of both a lack of knowledge of the surface features of the act and its harmful consequences.[71]

5.76 For example, a person who hits another person with a stick, but thinks they were actually hitting a tree, would not know the nature and quality of their conduct.

5.77 The circumstances in which an accused person does not know the nature and quality of their conduct are rare. The defence of mental impairment is most successful where the second limb of the M’Naghten test is established. This limb relates to the way in which the person processes knowledge about the nature and quality of their conduct and that it was wrong.[72]

Knowledge that the conduct was wrong

5.78 In Australia, the test for determining whether a person ‘knew what he or she was doing was wrong’ is a moral one rather than a legal one.[73] It is about a person’s ability to understand right from wrong.

5.79 The standard to be applied to the conduct is that of the ordinary person, ‘in the sense that [an] ordinary reasonable … [person] understand[s] right and wrong and that [as a result of a mental impairment] he was disabled from considering with some degree of composure and reason what he was doing and its wrongness’.[74]

5.80 A causal relationship is required between the mental condition and a person being unable to understand that their conduct was wrong.[75] This means that it must be because of the person’s mental impairment that they did not know that their conduct was wrong:

[I]f the disease or mental derangement so governs the faculties that it is impossible for the party accused to reason with some moderate degree of calmness in relation to the moral quality of what he is doing, he is prevented from knowing that what he does is wrong.[76]

5.81 The New South Wales Law Reform Commission has highlighted some of the issues with the Victorian approach, particularly regarding the requirement that the person be unable to consider their actions with ‘some degree of composure and reason’:

A problem with this approach is that it is based on an assumption that, in ordinary circumstances, a person acts (or refrains from acting) only after a reasoned assessment of the rights and wrongs of behaving in a certain way … In many cases where the defence of mental illness is based on a claim that the person did not know that the act was wrong, it is the extinction or impairment of subconscious regulation, not an inability to reason calmly, which accounts for the act being done (or, more correctly, the person’s failure to refrain from doing it).’[77]

5.82 While Victoria adopts the common law language of ‘knowledge’, other states such as South Australia, Tasmania, Queensland, Western Australia use a capacity-based knowledge requirement with a volitional element (that the accused person was unable to control their conduct).

5.83 Queensland requires that the accused person lack the capacity to understand what they are doing, control their actions or know that they should not do the act.[78] Western Australia employs a similar test, requiring the person be deprived of the capacity to understand, control and know that he ought not to do the act or make the omission.[79] Tasmania requires that ‘when such act or omission was done or made under an impulse which, by reason of mental disease, he was in substance deprived of any power to resist’.[80] South Australia requires that the person ‘is unable to control the conduct’.[81]

5.84 There is some contention over whether a ‘knowledge’ or ‘capacity’ approach is more restrictive.[82]

Questions

35 How does the test establishing the defence of mental impairment in the

CMIA operate in practice? Are the current provisions interpreted consistently by the courts?

36 If a definition of mental impairment were to be included in the CMIA, should it also include the operational elements of the M’Naghten test for the defence of mental impairment? If so, should changes be made to either of the operational elements?

37 Are there any issues with interpretation of the requirement that a person be able to reason with a ‘moderate sense of composure’?

Process for establishing the defence of mental impairment

5.85 The process for establishing the defence of mental impairment is set out above from [5.24]. As discussed, the mental impairment defence can be raised in the Supreme Court, the County Court or the Magistrates’ Court. In this section, the Commission will look at issues regarding the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment.

5.86 As part of this review, the Commission has also been asked to consider whether the Magistrates’ Court should be permitted to make supervision and other orders in relation to a person found not guilty because of mental impairment and this will be discussed in Chapter 6.

Issues in relation to the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment

5.87 In its preliminary research, the Commission has identified some possible issues regarding the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment. These primarily relate to the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment in the higher courts (the Supreme Court and County Court). The Commission would like input on the issues identified and any other issues that may exist regarding the operation of the process in any court level, including:

• the role of lawyers in the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment

• the role of experts in the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment

• jury involvement in the process and consent mental impairment hearings.

The role of lawyers in the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment

5.88 As discussed above, the defence of mental impairment can be raised at any time throughout the trial by lawyers.

5.89 Lawyers representing the accused person may face ethical issues in deciding whether to raise the defence of mental impairment. If the defence of mental impairment is successful, the accused person may be made subject to an onerous supervision regime for an indefinite period of time under the CMIA. Lawyers need to have a thorough understanding of the CMIA regime when providing advice to clients who may be eligible for the defence, to ensure the accused person appreciates the legal consequences.

5.90 Ethical issues may arise in cases where unfitness of the accused person is also in question and the accused person is unable to give instructions to their lawyer. Ethical issues arising over whether to raise the issue of unfitness are discussed in Chapter 4.

5.91 The outcome in terms of sentence is a key factor in the advice to and decision of an accused person in facing a charge (that is, whether to plead or raise the defence). Some accused persons may base their decision on whether to raise the mental impairment defence on advice about the consequences of the finding. If a lawyer advises an accused person that they are likely to receive a definite sentence within a particular range if they plead guilty, they may choose to do this over facing an indefinite supervision order.

5.92 On the other hand, an accused person may choose to raise the defence where there is a legitimate basis for avoiding criminal responsibility and sentence and be subject to a supervision order and receive treatment. As a person is highly reliant on their lawyer in these situations, it is essential that lawyers have a good working knowledge of the CMIA. For example, lawyers should understand that a supervision order is indefinite, what ‘nominal term’ means, and the restrictions that will be placed on a person’s liberty if they become subject to the regime. Lawyers must also understand how the CMIA provisions operate in practice.

Questions

38 What ethical issues do lawyers face in the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment?

39 What is the best way of addressing these ethical issues from a legislative or policy perspective?

The role of experts in the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment

5.93 As with the process of determining unfitness to stand trial, expert reports play an essential role in establishing the defence of mental impairment. However, while the court has the power to order a report to assist in determining unfitness to stand trial, they do not have similar powers in relation to the defence of mental impairment.

5.94 Similar issues to those outlined in Chapter 4 may arise in relation to the provision of expert reports to the court and the role of experts in establishing the defence of mental impairment. Possible issues include the qualifications of the experts, the quality and utility of expert reports and the number of reports relied on. The Commission is interested in gathering information about these potential issues and other issues in this area.

Question

40 Are there any issues that arise in relation to the role of experts and expert reports in the process for establishing the defence of mental impairment?

Jury involvement in the process and consent mental impairment hearings

5.95 The role of the jury is to determine whether the accused person was suffering from a mental impairment at the time of committing the offence. For example, if expert evidence indicates that the accused person was suffering from schizophrenia, the jury must determine if at the time of committing the offence, the accused person’s symptoms were consistent with schizophrenia.

5.96 In its defences to homicide reference, the Commission consulted on issues in relation to ‘by consent’ mental impairment hearings and considered that empanelling a jury in these cases was ‘both unnecessary and inappropriate’.[83] The Commission found that the role of the jury in these cases was not to make a determination on the evidence but to confirm the view of the defence and prosecution. The Commission therefore argued that the process of empanelling a jury where both the prosecution and defence agreed on the evidence that the defence of mental impairment had been established undermined the role of the jury and ‘may lead to a loss of faith in the jury system’.[84]

5.97 The CMIA was amended to allow for by consent mental impairment hearings.[85] If the prosecution and defence both agree that the evidence has established the defence of mental impairment, the trial judge may decide a jury is not required to make a determination.[86]

5.98 Instead, the trial judge alone may hear evidence and:

• direct that a verdict of not guilty because of mental impairment be recorded if the judge is satisfied on the evidence that the defence of mental impairment has been established,[87] or

• must direct that the person be tried by a jury if the judge is not satisfied on the evidence that the defence of mental impairment has been established.[88]

5.99 It is unclear whether a consent mental impairment hearing is available after a finding of unfitness as discussed in Chapter 4 from [4.110].

Question

41 Should there be any changes to the current processes for jury involvement in hearings and consent mental impairment hearings?

Directions to the jury on the defence of mental impairment

5.100 In the Supreme Court and County Court, a jury will determine if the defence of mental impairment has been established on the balance of probabilities.[89]

5.101 The Magistrates’ Court does not have juries and therefore the question of whether the defence of mental impairment has been established will be determined by the magistrate alone.

5.102 The Commission has been asked to consider whether legislative clarification is required as to how the law should provide for the jury to approach the elements of an offence, and any defences or exceptions, where the defence of mental impairment is an issue. The Commission considers these issues in this section.

Issues relating to directions to the jury

5.103 The Commission has identified in its preliminary research three main aspects on the issue of jury directions with regard to the mental impairment defence, as follows:

• The order of considering elements of an offence—whether a jury should be directed that the prosecution is required to prove all the elements of an offence before a jury can consider the defence of mental impairment, or directed that the prosecution need only prove certain elements of the offence and not the mental element before the jury can consider the defence of mental impairment.

• The relevance of mental impairment to the jury’s consideration of the mental element of an offence—whether a jury ought to be able to consider evidence of mental impairment (mental illness, intellectual disability or cognitive impairment) in determining whether the mental element of an offence has been proved beyond reasonable doubt.

• Legal consequences of findings—the extent of the trial judge’s obligation to direct the jury on the legal consequences of a finding of not guilty because of mental impairment.

5.104 Recent work in this area resulted in the Jury Directions Act 2013 (Vic), that aims to reduce the complexity of jury directions in criminal trials and to assist the trial judge to give jury directions in a manner that is as clear, brief, simple and comprehensible as possible.[90]

Order of considering the elements of an offence

5.105 An accused person is presumed not to be suffering from a mental impairment.[91] The defence of mental impairment may be raised by the prosecution or the defence, and the party raising the defence bears the onus of rebutting this presumption.[92]

5.106 A successful defence of mental impairment requires that it be proved on the balance of probabilities (that is more likely than not) that the accused person was suffering from a mental impairment that had the effect of the person not being criminally responsible for their action or omission.[93]

5.107 Traditionally, when a person is accused of an offence, all the elements of the offence must be proved beyond reasonable doubt.[94] The CMIA specifies that to establish the defence of mental impairment, it must be proved that the accused person engaged in conduct (an act or omission) that constitutes the offence.[95] The jury must specify whether a finding was based on a mental impairment defence where an accused person is found not guilty.[96]

5.108 Some offences have a mental element that must be proven in relation to an offence. Intention, knowledge, or recklessness are examples of mental elements that must be proved. In matters where mental impairment is an issue, it is currently unclear whether the prosecution must also prove the mental element of the offence first, prior to a jury being able to consider whether the person has a defence of mental impairment.

5.109 Currently in Victoria, there are two main approaches to directing juries in cases where mental impairment is an issue as cited in the charge book:[97]

• the approach taken in R v Stiles[98] (the Stiles approach)

• the approach taken in Hawkins v The Queen[99] (the Hawkins approach).

The Stiles approach

5.110 In the Victorian Court of Criminal Appeal case of R v Stiles (Stiles), the accused person, who had schizophrenia, was charged with manslaughter after assaulting a man with a piece of timber.

5.111 While this case did not detail the process by which the mental elements are to be considered in establishing the defence of mental impairment, it did comment on the order in which the jury should consider the elements of the offence.

5.112 The court in Stiles held that the jury must start with the presumption that the accused person does not have a mental impairment. The jury must then determine if all the elements of the offence have been proven, with the issue of mental impairment only considered if the prosecution succeeds in proving all elements of the offence. If the jury determines that the accused person did not commit the physical elements of the offence, the accused person will be acquitted. If the jury is satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the accused person did commit the physical elements of the offence, they may then consider evidence relating to mental impairment.[100]

5.113 The Stiles approach requires that the jury consider all the elements of the offence prior to making a determination about the existence of a mental impairment. This ensures that the accused person is able to obtain a complete acquittal if the jury is not satisfied that the prosecution has proved all the elements of an offence.[101]

5.114 This can be compared with an approach where the jury considers the defence of mental impairment first, prior to deciding whether the accused person even did the physical acts (the physical elements) that constitute the offence. Following this approach, the accused could be found not guilty because of mental impairment of an offence that they in fact did not commit. This could deny the accused person the right of an outright acquittal of the offence.

5.115 However, under the Stiles approach the jury may be required to employ artificial reasoning. This is because they must presume that the accused person is not mentally impaired when they consider whether the prosecution has proved both the physical and mental elements of the offence. At the same time, they may be hearing evidence (relevant to the mental elements) that the accused person has a mental impairment.

The Hawkins approach

5.116 The High Court of Australia in the case of Hawkins v The Queen (Hawkins) considered the interaction between mental impairment and voluntariness. In this case, the defence was that in a disturbed state of mind, the accused person intended to commit suicide but upon seeing his father, fired a gun and killed him instead without the specific intent to murder, which was the crime charged. The accused’s counsel did not raise the defence of insanity (under the Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas)) or wish that defence to be put to the jury. The court stated:

In principle, the question of insanity falls for determination before the issue of intent. The basic questions in a criminal trial must be: what did the accused do and is he criminally responsible for doing it? … It is only when those basic questions are answered adversely to an accused that the issue of intent is to be addressed.[102]

5.117 The approach stated by the High Court in Hawkins is that the jury is required to consider the physical elements first before turning to the question of whether an accused person has a mental impairment defence. Under this approach, once the jury has determined that the accused person did the physical acts and does not have a mental impairment defence, it can consider the question of whether they had the requisite level of intention.

The approach to jury directions in Victoria post Stiles and Hawkins

5.118 The case of DPP v Soliman[103] (Soliman) also raised the issue of the order in which the jury must consider the elements of the offence. The issue in this case was the approach that the jury was to take in considering the elements of the offence of rape and the defence of mental impairment.

5.119 The accused person in this case was charged in the County Court with one count of rape and pleaded not guilty. He had previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia, but expert evidence presented conflicting views as to whether the accused person qualified for a defence of mental impairment. The issue to be determined in this case was whether the accused person’s mental impairment resulted in him being unable to be aware if the complainant was not consenting to sexual intercourse.

5.120 The court decided that Stiles provided the correct approach for considering the order of the elements of the offence in this case. The judge outlined the reasons for this decision as follows:

• Hawkins did not consider the case of Stiles and therefore did not overrule it

• Hawkins, a High Court decision, considered provisions of the Tasmania Criminal Code rather than the common law and therefore the court was not bound to follow it

• the Stiles approach was followed in the case of R v Fitchett [104] (Fitchett) without any complaint in the Court of Appeal

• it was agreed by the parties that the Stiles approach was most appropriate because if the Hawkins approach was adopted, the jury might never reach consideration of the fourth element of rape and therefore the accused person may be deprived of a chance of being acquitted

• the Stiles approach is consistent with section 20 of the CMIA, that sets out the defence of mental impairment.[105]

5.121 The Court held that ‘in assessing whether the Crown has proven beyond reasonable doubt that the accused [person] was aware that the complainant was not consenting, might be consenting, or failed to give any thought as to whether or not the complainant was consenting, the jury will not be directed to consider the accused’s mental illness’.[106] The approach in this case was outlined as follows:

• if the jury is satisfied beyond reasonable doubt of all the elements of rape, but is not satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the defence of mental impairment has been established, the accused person will be criminally responsible for the offence

• if the jury is satisfied beyond reasonable doubt of all the elements of the offence of rape (absent evidence of mental impairment) and is also satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the accused person was mentally impaired at the time of the offence, the accused person will be found not guilty because of mental impairment

• if the jury is not satisfied beyond reasonable doubt of all the elements of the offence of rape, the accused person will be acquitted.[107]

The approach in other jurisdictions

5.122 In Western Australia, the issue of how the jury should approach the elements of the offence was considered in the case of Ward v The Queen (Ward). In this case it was held that it is the directions which are provided to the jury which are important, rather than the order in which the elements are approached:

Provided that all defences open to an accused are the subject of proper directions, and all elements of the offence are canvassed, it has not as I understand it been suggested that it is necessary, as a matter of law, that directions consider particular matters in any particular order.[108]

5.123 The view in Ward was endorsed in the case of Stanton v The Queen where it was held that the judge has discretion in directing the jury on how to approach the elements of the offence:

there is no rule of law or practice that requires a trial Judge to direct a jury that they must consider (as opposed to decide) on various alternative offences that are open on an indictment in any particular order. The trial Judge may do so if he or she thinks that the facts of the case so require and that it will assist the jury to do so. But the power of the jury to approach the task in whatever way they see fit must be respected. If such a direction is given it should be made clear that it is directory or permissive rather than mandatory.[109]

5.124 In 2007, the Western Australian Law Reform Commission agreed with the position in Ward and Stiles. It recommended that legislation should not outline the procedure to be followed for a jury considering the elements of a mental impairment defence. In doing so, it said:

The Commission agrees with the reasons for decision of Wheeler and Pidgeon JJ in Ward who stated that, so long as correct directions are given to the jury in respect of the relevant burden of proof and other matters in relation to each issue, there is no reason to require a trial judge to direct a jury to consider the questions of intent and insanity in a particular order.[110]

5.125 Consistent with the Western Australian approach, in South Australia, legislation provides that the trial judge has the discretion to decide on the order in which the objective and subjective elements of the offence are to be considered. The legislation outlines options for the procedure to be followed, depending on which elements of the offence are to be considered first.[111]

5.126 In New Zealand, the judge or jury only considers the issue of mental impairment once the Crown has proven that the act was committed. As stated in R v Cottle:

This is for the reason that the jury would only go on to consider the special defence, if it were already convinced that the Crown had proved to its complete satisfaction that the act had been committed by the prisoner and—if he was sane—in circumstances which compelled the conclusion that the act was deliberate and intentional.[112]

Questions

42 What approach should be adopted in directing juries on the order of the elements of an offence in cases where mental impairment is an issue?

43 Should the trial judge be required to direct the jury on the elements of an offence in a particular order where mental impairment is an issue?

The relevance of mental impairment to the jury’s consideration of the mental element of an offence

5.127 A separate but related consideration to the issue of the order of offence elements is whether the accused person’s mental impairment is relevant to the jury’s consideration of the mental element of an offence.

5.128 This issue has been identified as arising in particular under the Stiles approach to directing the jury on offence elements.

5.129 Under the Stiles approach to directing a jury, the jury would first have to determine if all the elements of the offence have been proved, including the mental element of the offence. It is only after all the elements of the offence have been proved that the jury would consider evidence relevant to the defence of mental impairment. However, if there is evidence that the accused had a mental impairment at the time of the offence, this could be relevant to the accused person’s state of mind at the time of the offence. If there is such evidence, even if it falls short of establishing the mental impairment defence, the prosecution may be unable to prove the mental element of the offence because the accused person was suffering from a mental impairment.

5.130 The issue therefore centres on the uncertainty as to whether evidence of an accused person’s mental impairment is to be used by the jury to either:

• find that the impairment prevented the accused from forming the requisite mental element for the offence and therefore the element is not proved at all and completely acquit the person, or

• find that the mental element is proved, but that the impairment prevented the accused from having the capacity to know the nature and quality of their actions or to know whether it was right or wrong, and therefore find the accused person not guilty because of mental impairment.

5.131 A number of trial judges have drawn attention to the uncertain state of the law on this issue and the consequent difficulty in properly instructing juries.[113] In the case of Soliman, this issue arose in the context of whether evidence of the accused person’s mental illness could be used to determine whether the fourth element of the offence of rape (awareness that or not giving any thought to whether the complainant is not consenting or might not be consenting), had been proved by the Crown beyond reasonable doubt. The court held that:

If an accused is to be presume[d] to be of sound mind for the purposes of a jury’s consideration of all the elements, then evidence which goes to the issue of mental impairment, whether it be evidence supporting the defence or rebutting it, should only be considered if, and when all the elements of rape, are proven. If this were otherwise, then potentially all the same evidence which would be relied upon to establish, or even rebut the defence of mental impairment, may well result in an accused’s outright acquittal and would interfere with the presumption of sound mind. This would potentially undermine the Stiles approach and undermine the province of the defence of mental impairment itself.[114]

5.132 The High Court in Hawkins stated that evidence of ‘mental disease’ (under section 16 of the Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas)) is relevant to specific intent where this is not sufficient to amount to a defence of insanity.[115]

Question

44 What approach should be adopted in determining the relevance of mental impairment to the jury’s consideration of the mental element of an offence?

Legal consequences of the findings

5.133 Where a jury has been empanelled and there is evidence that raises the defence of mental impairment, the judge must direct the jury to consider this issue.[116] The judge must also explain to the jury the possible findings and the legal consequences of those findings.[117]

5.134 It is not the usual practice in a criminal trial to explain the legal consequences of the findings to the jury. This is consistent with the ‘well-established view of the jury role’ in a criminal proceeding.[118] If a judge is required to explain what may happen to the accused person after the trial, this may affect the outcome of the trial.

5.135 The purpose of introducing the requirement to explain the legal consequences of findings to the jury arose out of concerns that juries may be reluctant to make a finding of not guilty because of mental impairment, if they believed ‘it could result in the immediate release of a disturbed and dangerous person when, as a practical proposition in most cases, that would most certainly not be the case’.[119]

5.136 In the case of Fitchett, the Court of Appeal considered whether the trial judge had properly instructed the jury in relation to the consequences of the legal findings. Fitchett was accused of the murder of her two sons and raised the defence of mental impairment. The Court of Appeal held that instructions to the jury require something more than a recitation of the possible orders that can be made, as this may ‘not be either informative or serve to allay the perceived fears of jury members’.[120] It was held in this case that the jury directions on the legal consequences were deficient as they constituted a description of procedure rather than consequences and while the jury was told there would be consequences, no further explanation was provided.

5.137 Fitchett also highlighted tensions that judges must manage when directing juries on the legal consequences of findings. Difficulties arise when judges seek to reassure the jury that the accused person will not be released when this is a possible outcome in the legislation. This has created difficulties for judges in determining what is required when directing the jury on the legal consequences of the findings:

Perusal of a number of recently delivered charges in the Trial Division of the court has revealed that there is some confusion concerning what should or should not be said in this regard and the difficulty which has been encountered in resolving the tension. Judges generally appear to have been concerned to reassure jury members that the verdict would not result in the release of the person into the community.[121]

Question

45 Are changes required to the provision governing the explanation to the jury of the legal consequences of a finding of not guilty because of mental impairment?

Appeals against findings of not guilty because of mental impairment

Current law

5.138 A person may appeal a verdict of not guilty because of mental impairment to the Court of Appeal, after obtaining leave (permission) from the Court of Appeal.[122]

5.139 The Court of Appeal must allow an appeal if it is satisfied that:

• the verdict is unreasonable or cannot be supported by the evidence

• as a result of an error or an irregularity in the trial, there has been a substantial miscarriage of justice, or

• there has been a substantial miscarriage of justice for any other reason.[123]

5.140 If the Court of Appeal allows an appeal because it thinks that the verdict of not guilty because of mental impairment should not stand or considers that the proper verdict should have been guilty of an offence, it may substitute the verdict for a verdict of guilty.[124] Otherwise, if the Court of Appeal allows the appeal, it must set aside the not guilty because of mental impairment verdict and enter a verdict of acquittal or order a new trial.[125]

Principles underpinning appeals

5.141 As discussed in Chapter 4 at [4.138], appeals serve an important function. They provide an opportunity for a higher court to review a decision of a lower court and correct any errors that have been made, to protect against miscarriages of justice, maintain consistency between trial courts and provide legitimacy to the criminal justice system.

5.142 Information currently available to the Commission indicates that appeals against findings of not guilty because of mental impairment are infrequent in Victoria. As noted at [4.140], the same observation has been made about appeals against findings of unfitness.

Question

46 Are there any barriers to accused persons pursuing appeals in relation to findings of not guilty because of mental impairment?

-

Victorian Law Reform Commission, Defences to Homicide, Final Report (2004) 171.

-

Desmond O’Connor and Paul A. Fairall, Criminal Defences (Butterworths, 3rd ed, 2006) 12.

-

See Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) s 5(1).

-

R v Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182, 186.

-

New South Wales Law Reform Commission, People with cognitive and mental health impairments in the criminal justice system: criminal responsibility and consequences, Consultation Paper No 6 (2010) 50.

-

Ibid 47.

-

R v Hadfield (1800) 27 State Tr 1281.

-

Daniel M’Naghten’s Case (1843) 8 ER 718.

-

Ibid 722.

-

Stanley Yeo,’Commonwealth and International Perspectives on the Insanity Defence’ (2008) 37 Criminal Law Journal 7, 9.

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 25.

-

Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 18 September 1997, 187 (Jan Wade, Attorney-General).

-

R v Sebalj [2003] VSC 181 (5 June 2003) [14].

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) ss 20(1)(a)–(b).

-

Director of Public Prosecutions, Director’s Policy – The Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried Act 1997 – Unfitness to Stand Trial and the Defence of Mental Impairment (2011).

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 20(1)(b).

-

Ibid s 21(1).

-

Ibid s 22(1).

-

Ibid s 21(3).

-

Ibid s 21(2).

-

Ibid s 21(4)(a).

-

Ibid s 21(4)(b).

-

Ibid s 23.

-

Ibid s 5(2).

-

Bernadette McSherry and Bronwyn Naylor, Australian Criminal Laws: Critical Perspectives (Oxford University Press, 2004) 53 (citations omitted).

-

Ibid 53.

-

Victorian Law Reform Commission, above n 1, 252, 262.

-

Ibid 126–7.

-

Ibid 233.

-

Ibid 243.

-

Daniel M’Naghten’s Case (1843) 8 ER 718, 722 [210].

-

R v Falconer (1990) 171 CLR 30, 53; R v Radford (1985) 42 SASR 266.

-

R v Radford (1985) 42 SASR 266.

-

Stephen Allnutt, Anthony Samuels and Colman O’Driscoll, ‘The Insanity Defence: From Wild Beasts to M’Naghten’ (2007) 15(4) Australasian Psychiatry 292, 297.

-

Ibid 295.

-

R v Radford (1985) 42 SASR 266, 274.

-

R v Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182, 189.

-

Ibid 188.

-

Judicial College of Victoria, Victorian Criminal Charge Book (23 April 2013) <http://www.judicialcollege.vic.edu.au/eManuals/CCB/index.htm#19057.htm>.

-

R v Falconer (1990) 171 CLR 30; R v Radford (1985) 42 SASR 266.

-

R v Hughes (1989) 42 A Crim R 270; Nolan v R (Unreported, Court of Criminal Appeal, 22 May 1997).

-

R v Kemp [1957] 1 QB 399; R v Radford (1985) 42 SASR 266.

-

Judicial College of Victoria, above n 39.

-

R v Scott [1967] VR 276; R v Wogandt (1983) 33 A Crim R 31.

-

R v Sebalj [2006] VSCA 106 (2 May 2006); R v Whelan [2006] VSC 319 (27 April 2006).

-

Some cases of dissociation and epilepsy have been found to constitute a mental impairment while other cases have not. See R v Falconer (1990) 171 CLR 30 (Deane and Dawson JJ).

-

R v Hennessy [1989] 1 WLR 287.

-

For hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar) see R v Quick [1973] QB 910 and hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) see August v Fingleton [1964] SASR 22.

-

New South Wales Law Reform Commission, above n 5.

-

Steven Yannoulidis, Mental State Defences in Criminal Law (Ashgate, 2012) 63–4.

-

Community Development Committee, Parliament of Victoria, Inquiry into Persons Detained at the Governor’s Pleasure (1995) 172.

-

Ibid 151.

-

Ibid 212.

-

McSherry and Naylor, above n 25, 531.

-

Community Development Committee, above n 51, 208–9.

-

Victorian Law Reform Commission, above n 1, 217.

-

Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) s 7.3(8).

-

Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) s 269A; Criminal Code Act 1913 (WA) s 1(1); Criminal Code 2002 (ACT) s 27(1); Criminal Code Act (NT) s 43A.

-

Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s 27; Criminal Code 1924 (Tas) s 16.

-

Community Development Committee, above n 53, 149.

-

Ibid 152.

-

Law Reform Commission of Victoria, Mental Malfunction and Criminal Responsibility, Report No 34 (1990) 18.

-

Law Reform Committee, Parliament of Victoria, Inquiry into Access to and Interaction with the Justice System by People with an Intellectual Disability and Their Families and Carers (2013) 243.

-

Ibid.

-

Victorian Law Reform Commission, above n 1, 207.

-

Ibid 209. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the major accepted diagnostic tool for mental illness and other mental disorders. The fifth edition (DSM-5) was released on 22 May 2013.

-

Yannoulidis, above n 50, 65.

-

R v Codere (1917) 12 Cr App R 21.

-

Sodeman v R (1936) 55 CLR 192.

-

R v Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182, 189.

-

Yannoulidis, above n 50, 15 (citation omitted).

-

Ibid 16.

-

Stapleton v R (1952) 86 CLR 358.

-

R v Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182, 190.

-

Ibid 189.

-

Sodeman v R (1936) 55 CLR 192, 215.

-

New South Wales Law Reform Commission, above n 5, 68.

-

Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) s 27.

-

Criminal Code Act 1913 (WA) s 27.

-

Criminal Code 1924 (TAS) s 16(1).

-

Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) s 269C.

-

See Yeo, above n 10; New South Wales Law Reform Commission, above n 5, 69.

-

Victorian Law Reform Commission, above n 1, 229.

-

Ibid 230.

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 21(4).

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid s 21(4)(a).

-

Ibid s 21(4)(b).

-

Ibid s 21(2)(b).

-

Jury Directions Act 2013 (Vic) s 1.

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 21(1).

-

Ibid s 21(3).

-

Ibid s 21(2)(b).

-

R v Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182; Stapleton v R (1952) 86 CLR 358; Sodeman v R (1936) 55 CLR 192.

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 20(1).

-

Ibid s 22(2)(b).

-

Judicial College of Victoria, above n 39.

-

R v Stiles (1990) 50 A Crim R 13.

-

Hawkins v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 500.

-

R v Stiles (1990) 50 A Crim R 13, 22.

-

Ibid.

-

Hawkins v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 500, 517.

-

DPP v Soliman [2012] VCC 658 (1 May 2012).

-

R v Fitchett (2009) 23 VR 91.

-

DPP v Soliman [2012] VCC 658 (1 May 2012) [24].

-

Ibid [61].

-

DPP v Soliman [2012] VCC 658 (1 May 2012) [63]–[64].

-

Ward v The Queen (2000) 23 WAR 254 [130].

-

Stanton v The Queen [2001] WASCA 189 (22 June 2001) [84].

-

Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Review of the Law of Homicide, Final Report (2007) 237.

-

Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) ss 269F, 269G.

-

R v Cottle [1958] NZLR 999, 1030.

-

See, eg, Transcript of Proceedings, R v Sutherland (County Court of Victoria, CR-10-00016, Judge Punshon, 18 October 2012) 118.

-

DPP v Soliman [2012] VCC 658 (1 May 2012) [41].

-

Hawkins v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 500, 517.

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 22(2).

-

Ibid s 22(2)(a).

-

R v Fitchett (2009) 23 VR 91, 100.

-

Ibid 102.

-

Ibid 103.

-

Ibid.

-

Crimes (Mental Impairment and Unfitness to be Tried) Act 1997 (Vic) s 24AA(1).

-

Ibid s 24AA(4).

-

Ibid s 24AA(7).

-

Ibid s 24AA(8).

|

|